Historically, Jaipur’s energy has always arched from its royal residence into the 300-year-old warren we call the Pink City. In recent years, Gen Z royals HH Padmanabh Singh and Princess Gauravi Kumari have kept that current alive, channelling it from their family seat at the City Palace, Jaipur, to the streets.

A few lanes from the palace, amid historic jewellery ateliers, The Johri at Lal Haveli reset the city’s hospitality code in 2020. Set inside a 350-year-old haveli and led by hotelier Abhishek Honawar, The Johri proved that intimate, design-forward luxury can out-charm palatial hotels and teach them a thing or two in the hospitality game.

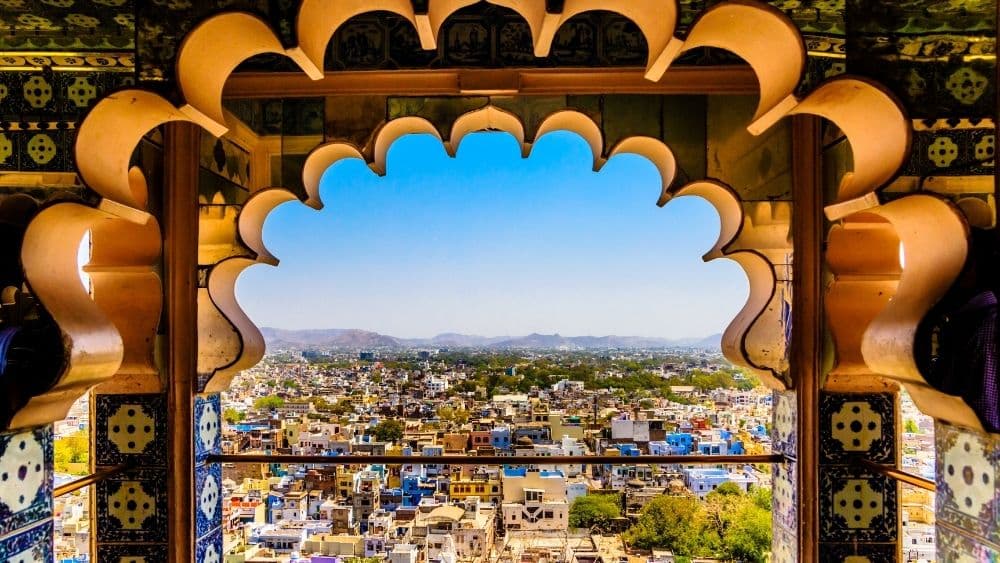

From the courtyards of palaces and havelis to a single rooftop of a palatial premises, Singh and Honawar now converge under one address: Sarvato. Named for a perfect square, it occupies an erstwhile royal court with a terrace that stares directly at the City Palace, an angle usually off-limits to visitors. The brief is disarmingly simple: change Jaipur’s culinary game.

For a city defined by the custom of manuhar, to serve lavish spreads and abundance, a six-course tasting menu is a quiet revolution. Bite-sized courses are now common in larger Indian metros, but for Jaipurites and travellers who think they know Rajasthani food, Sarvato is a reset.

The team tested the waters in January 2025, around the Jaipur Literature Festival. The terrace drew celebrities, media, and the city’s style set; then it closed for the summer. This winter, Sarvato reopens with a bigger statement: it joins Relais & Châteaux, aligning with a guild that champions independent, place-rooted properties and exacting standards, from sourcing to service and hospitality craft.

Among stand-alone restaurants in India under the Relais & Châteaux umbrella, Sarvato keeps rare company and is only the second address. Masque in Mumbai, the first, needs no introduction.

Joerg Drechsel, Relais & Châteaux Delegate for Indian Subcontinent & Southeast Asia & Owner of The Malabar House, India says, “Our affiliation process is rigorous: each candidate undergoes anonymous inspections to ensure they meet our standards of excellence in service, cuisine, and cultural immersion. Once part of our family, all restaurants gain access to a global network of over 580 properties, allowing them to make global connections, put forward their unique dining experiences, and reach discerning travellers worldwide. Relais & Châteaux represents the largest network of gastronomic restaurants in the world, including a total of 372 Michelin stars."

While Mumbai’s Masque reimagines Indian cooking to build cross-cultural bridges, Sarvato channels Rajasthan like lifeblood. The menu is unapologetically rooted in desert soil: salt drawn from nearby Sambhar Lake, fiery Mathania chillies, and kebabs shaped from local millets.

Food at Sarvato

Across six courses, the seemingly usual gets a Michelin-style makeover. Gwar fali (cluster beans) arrives with crisp, fried hauteur. Ghevar is a festive stack stuffed with boondi and doubled with malai. The city’s beloved savoury Raj Kachori lands in a deliberately petite form: cute, yes, but complete, its dozen essentials compressed into half a bite. The effect is an explosion of taste notes: sweet, tangy, crunchy, and spicy, all together at once.

Sarvato honours tradition. Today’s Indian Gen Z may be obsessed with sourdoughs and fancy loaves. Here, a small, homemade phulka (a Home-Style Indian Bread) is rolled and puffed beside you by two local women from the City Palace kitchens, served just the way your mother might. For the final savoury flourish, Chawal-ke-Dawat: rice may be everyday elsewhere in India; in Rajasthan, it is celebratory. The course is long-grained basmati rice topped with a kofta stuffed with Jaipur’s famous zero-size peas, with a side of Bikaneri papad.

The story of Sarvato is not just the Rajasthani tradition of everyday homes. As one can expect, some royal recipes, hushed or forgotten, such as battakh ka mokul and deg ka laal maas, come straight from the royal kitchens.

Abhishek Honawar says, “Indian food, if served as is, has scope to play around with flavours. We can tear the phulka, top it up with gravy, add some pickle and mirch ki tapora to finish it. Another bite can be totally different. That is the beauty of Indian food. We wanted global travellers, or the next generation who have forgotten to do this, to experiment and customise every bite.”

Shatranj ki Bisaat, course number two, is a brilliant way to do it. Served in a box-like mezze platter with all-Indian ingredients, local, seasonal pickled vegetables, such as carrots and radishes, can be dipped in homemade butter and topped with masala jaggery. The pull-apart bread is made from bejad (a mix of many flours, a popular staple in the state) and is finished with cow’s ghee.

Sarvato plays with nostalgia as with food. The kachori comes in a small brass tiffin, and the main course in a grandmother’s treasure chest called a Sandook. The names of the courses are earthy, such as Safar ka Dabba and Niwala.

The price tag is Rs 8,000 plus tax, excluding alcohol, and for Jaipur, this is also unfamiliar for a stand-alone restaurant. But Sarvato is a celebratory place. You are, after all, at the heart of Jaipur, gazing at a residential royal palace from an almost illicit distance. You are eating recipes from both the historical past of everyday Jaipur and the royal kitchens, perhaps even some of HH Padmanabh Singh’s favourites. If you are lucky, you might spot him seated casually on one of the bar stools. It is as royal, and as Jaipur, as it can get, all in one dinner, one place, and one night.